Grapes Burn Acid to Save Sugar

The chemistry behind the drop in acid during ripening.

What a UPS is for

A UPS is an uninterruptible power supply.

If you work from home and occasionally lose power, you either have one or you should get one. It’s the heavy, black box that sits under a desk or next to a router, quietly doing nothing most of the time, until the power goes out.

A UPS isn’t designed to power everything in your house. It’s designed to protect the things that need to stay on when the grid goes down. It switches automatically to a different power source, not because that power source is better or more efficient, but because it preserves what matters most. It’s a system built around priorities.

Choosing what stays on

I have one at home, and there are a few things I’ve intentionally plugged into it. My modem and Wi-Fi, for example. There are other things I could run off it in a pinch, like grinding coffee beans and brewing a pot, but those are choices. They would drain the battery faster, and one could argue they’re not essential.

When you don’t know when the power is coming back, you have to decide what’s critical and what’s optional.

Grapes, plugged into the grid

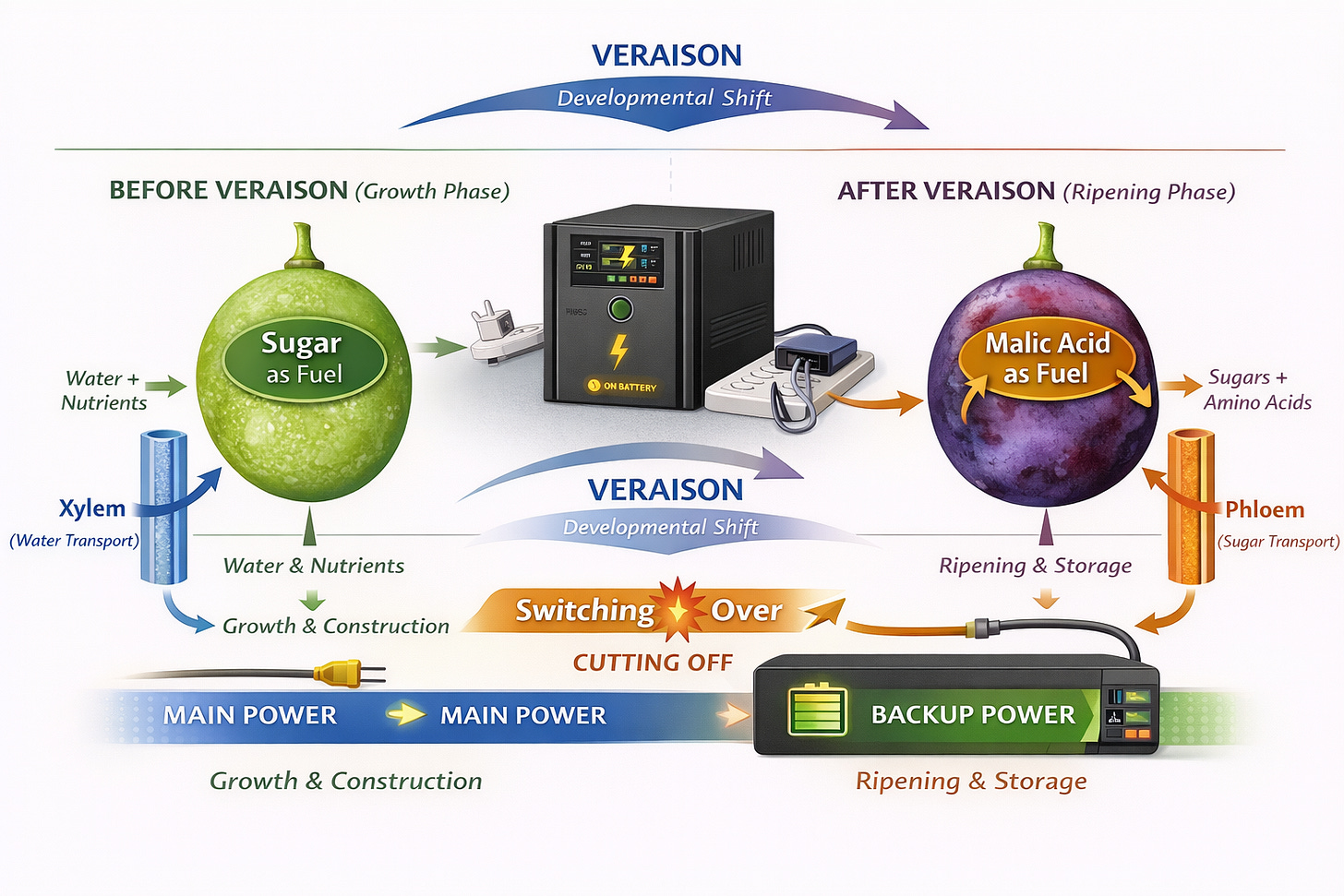

It turns out grapevines face a very similar decision.

Up until a certain point in the growing season, grapes are effectively plugged into the grid. Water and minerals flow in through the xylem. Inside the berries, cells are growing and dividing, acids are accumulating, and the whole system is focused on building structure rather than storing value.

Veraison, when priorities change

At veraison, priorities shift.

The berries soften. Color changes. Sugar begins to arrive in earnest. And at that moment, sugar stops being just another energy source and becomes the product.

Burning sugar to keep the berry alive during ripening would be like filling a bathtub while the drain is open. Water goes in, water goes out, and you never quite get full.

The system technically works, but it defeats the purpose.

Why malic acid?

Malic acid doesn’t suddenly appear so it can be burned during ripening. It’s been there all along, just like the UPS.

Early in the season, the grape is focused on growth. Cells are dividing and expanding, tissues are fragile, and the berry is managing water, pressure, and basic metabolism long before sugar is part of the picture. Malic acid supports that work. It helps regulate internal balance, stabilizes growing cells, and provides metabolic flexibility while the berry is still under construction.

By the time veraison arrives, the problems malic acid was solving are no longer the most important, since growth is finished and storage becomes the priority. The acid that once helped the berry grow becomes something the vine can afford to spend.

This is the grape’s UPS switching on.

Malic acid as backup power

Malic acid becomes the backup power supply that keeps critical metabolic functions running while sugar is protected and stored. Acid doesn’t disappear by accident during ripening. It’s being spent on purpose.

A UPS isn’t about efficiency, it’s about continuity. It runs on a different chemistry, has a limited fuel supply, and is designed to protect essential functions.

In grapes, the mapping looks like this:

Sugar is the protected load.

Malic acid is the backup fuel.

Ripening is the planned outage where priorities change.

Warm nights make the UPS run harder. Cool nights let it idle. That’s why climate shows up so clearly in acidity.

What this explains in the glass

Once you see ripening this way, a lot of familiar differences stop feeling mysterious. High-acid wines from cool climates, and low-acid wines from hot regions aren’t accidents. They’re the outcome of how long the backup system was left to run.